“You entered the country illegally”, said an immigration officer to Amy, when we were leaving the country. Definitely not something you want to hear when departing Guatemala, a small Central American country that our group visited for 6 days.

These used to be Cirrus-only trips, which started as COPA trips, but over time became independent. This year, we had 8 SR22s, two SF50s, and one Piper Malibu. Although Tino, the Piper owner used to fly a Cirrus, so he didn’t feel completely out of place. We limit the group size to twelve airplanes, but the twelfth developed a last-minute medical issue and grounded himself as PIC, which didn’t prevent him from joining us in Tikal traveling on commercial flights. My wife Ania and I organized already 10 of these trips, until then to Mexico, this was our first venture to Central America.

Departure

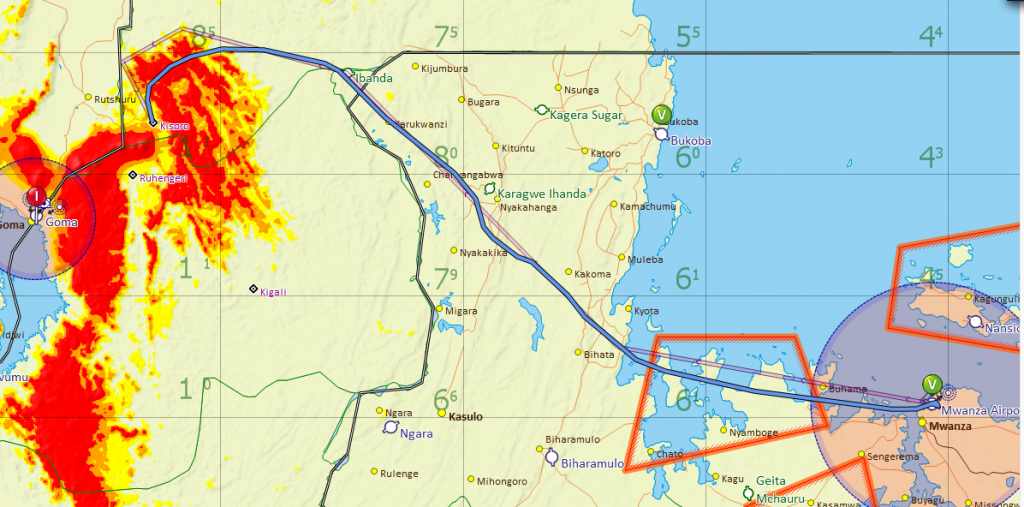

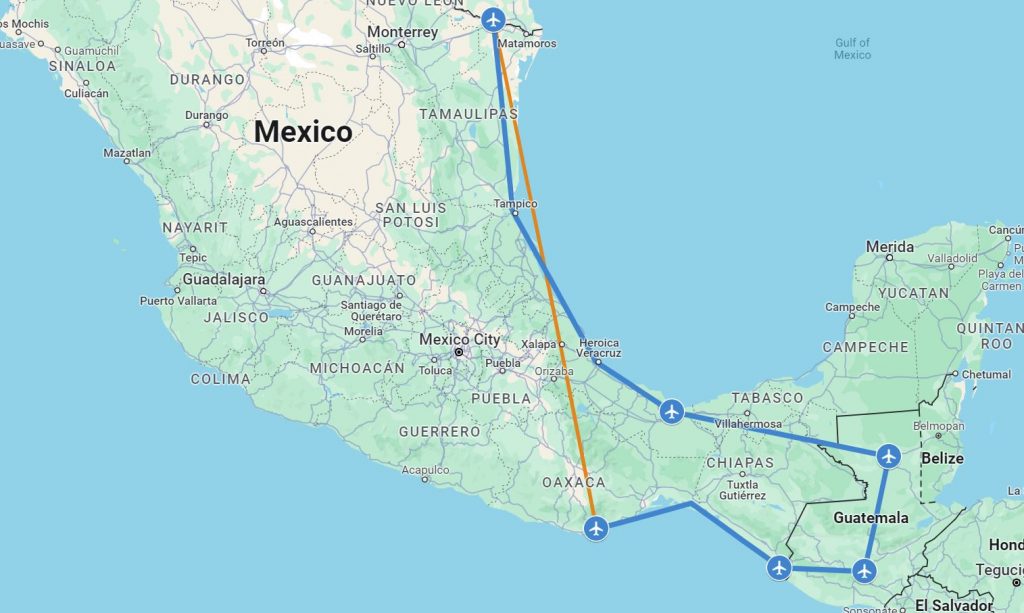

Our first stop, Tikal is a Mayan archeological site located in the Eastern part of Guatemala, close to Belize. To get there, our group met in McAllen, TX on a Saturday afternoon and departed on Sunday morning for our fuel stop in Minatitlan, Mexico. In January 2024, Mexico changed its entry procedures, which could create significant havoc when a group of 11 airplanes arrives at the same time. Before departure, you must send the required documents to the Airport of Entry. These include airplane airworthiness certificate, registration, pilot and medical certificates, copy of insurance policy, and the so-called LOPA. If you google that term, you will find out that it is Layout of Passenger Accommodations and it is an engineering diagram of the aircraft’s cabin interior that includes, but is not limited to, locations of passenger and flight attendant seats, emergency equipment, exits, lavatories, and galleys. Right, for a SR22! With typical Mexican efficiency, they don’t publish email addresses where this should be sent, you are on your own treasure hunt to find it. In addition, you are supposed to send to Mexican immigration services a monster Excel spreadsheet, which serves as an APIS entry document. And resend it “30 minutes prior to door closed”. I highly recommend joining Baja Bush Pilot or using the services of Flashpass.net to help navigate that madness.

In this case, since we organized the trip, we had a local contact in Minatitlan, to whom we sent all documents and who arranged for the so-called Autorización de Internación Única to be prepared. You would think that since AIU is Unica, it is for one entry into Mexico, but no, it is valid for multiple entries during 180 days. At least for now, it might change by the time you read. While our AIUs were all ready, the handler we used didn’t think about preparing our necessary exit documents since we were only stopping for fuel and continuing to Guatemala. Most countries have a concept of a “technical stop” for refueling, where the airplane occupants do not leave the airport, and which allows to skip entry/exit immigration procedures, but not Mexico. It would be foolish to skip the required administrative tasks and associated fees, wouldn’t it?

Altogether, we spent a little over two hours in Minatitlan and departed for Mundo Maya airport in Guatemala. Most of us flew both legs under IFR, the weather was making it preferable, but one pilot was not instrument-rated and managed to get through VFR. Our handlers were very efficient at Mundo Maya and we breezed through immigration and customs very quickly.

Tikal

Our first hotel was called Las Lagunas and consisted of beautifully decorated individual bungalows on a small lake next to Lago Petén Itzá. We arrived there in the late afternoon and stayed in the hotel for dinner to launch a visit to Tikal the next day.

Tikal site dates back to 1000 BC, at the peak of its glory, around 750 AD, it was home to at least 60,000 Maya and held sway over several other city-states scattered through the rainforest from the Yucatán Peninsula to western Honduras. At that time, “downtown” Tikal was about six square miles, though research indicates that the city-state’s population may have sprawled over at least 47 square miles. Today much of the city is still buried under the forests and overgrowth, but what has been excavated shows an elaborate and huge ancient Maya city with beautiful, crumbling temples and ruins around every corner.

We started the visit at the most spectacular attraction of the city, the Great Plaza, home to palaces, ceremonial buildings, stelae, carved altars, and the two giant pyramids known today as Temple I and Temple II. The magnificent Temple I is 154 feet high, dedicated to Lord Jasaw Chan K’awil who died in the year 734 AD. Also known as the Temple of the Great Jaguar, the impressive structure had its pyramid added approximately 10 years following the death of the king.

Believed to have been erected in the year 700, the adjacent Temple II, known as the Temple of the Mask, was constructed on the orders of Kasaw Chan K’awil. Deciphering the hieroglyphics in the structure, it is believed that Lord K’awil had the temple built for his wife, Lady 12 Macaw, although no tomb or human remains have been discovered inside. Lady 12 Macaw’s pyramid reaches 125 feet to the sky overhead. It is precisely oriented toward the rising sun, giving visitors an unparalleled view of the rest of the city and the surrounding jungle.

With private guides, we toured Complex Q and R, Temples I, II, III, and IV, Plaza Central, Central and North Acropolis, and Mundo Perdido.

Lake Atitlan

The following day, we drove back to the airport and departed for a short 150 nm hop to Aurora airport in Guatemala City, before boarding a bus to drive to Lago de Atitlán as it’s known in Spanish, which is one of the most beautiful lakes in all of Central America and is surrounded by three massive volcanoes – Tolimán, San Pedro, and Atitlán. The lake has an area of 50 square miles, and the color of its waters varies from deep blue to green. Formed approximately 84,000 years ago as a result of a volcanic eruption, it is 4,500 feet above sea level, with a length of 12 miles, and a depth of up to 1000 feet, making it the deepest lake in Central America. The shores of the picturesque lake are dotted with Indian villages, with the main towns Panajachel, Atitlán, and San Lucas.

Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World wrote in his travel book Beyond the Mexique Bay published in 1934, “Lake Como, it seems to me, touches on the limit of permissibly picturesque, but Atitlán is Como with additional embellishments of several immense volcanoes. It really is too much of a good thing.”

We stayed in Casa Palopó, an exceptional hotel that is part of the prestigious Relais & Chateaux, and had dinner in the hotel.

The following day, we met our private guide at Casa Palopó dock for a boat ride to experience the Maya culture and impressive views the lake offers. We visited San Juan La Laguna, learned about traditional dye with natural colors at the textile workshop, and visited the local art galleries.

Antigua

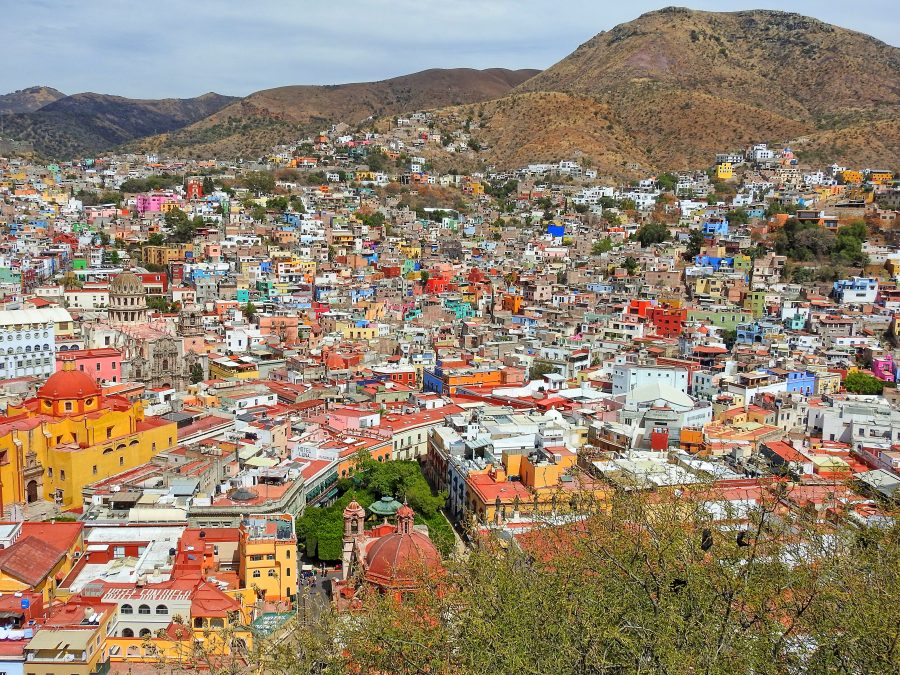

This was already the fourth day in Guatemala, and we boarded a bus again for a ride to Antigua, the ancient capital of the country. Founded in the early 16th century, Antigua served as the capital of the Captaincy General of Guatemala for 230 years. It survived natural disasters of floods, volcanic eruptions, and other serious tremors until 1773 when the Santa Marta earthquakes destroyed much of the town. At this point, authorities ordered the relocation of the capital to a safer location region, which became Guatemala City, the county’s modern capital. Some residents stayed behind in the original town, however, which became referred to as “La Antigua Guatemala”.

The city was revived in the mid-1800s, as a center of coffee and grain production. Now, the city’s cobbled streets — arranged in an easy-to-navigate grid, with views of the imposing Volcán de Agua to the south and the twin peaks of Volcán de Fuego and Acatenango to the west — are lined with farm-to-table restaurants, contemporary art galleries and design studios. We stayed in one of the best hotels in Antigua, El Convento Boutique Hotel.

The pattern of straight lines established by the grid of north-south and east-west streets and inspired by the Italian Renaissance is one of the best examples in Latin American town planning and all that remains of the 16th-century city. Most of the surviving civil, religious, and civic buildings date from the 17th and 18th centuries and constitute magnificent examples of colonial architecture in the Americas. These buildings reflect a regional stylistic variation known as Barroco Antigueño.

We explored the city with a private guide. The walking tour focused on the city’s history, cultural trends, and restoration efforts. We saw the City Hall Palace, Fountain of the Sirens, Royal Palace, visited San Jose Catedral and its ruins, and learned about Maya archeology at the Maya Jades Museum, completing the tour at the best museums in town at Paseo de los Museos.

The following morning we took a bus for a short drive to Finca Filadelfia for a group-guided visit to one of the oldest and most established coffee estates in Guatemala. We were able to follow the path of the coffee bean from the nursery to a cup and concluded with an educational tasting.

In the afternoon, we had an opportunity to visit Pacaya Volcano National Park and a horse ride up the volcano with a plan to watch incredible views, which unfortunately didn’t materialize due to clouds.

Return

This was our last day in Guatemala, and it was time to launch for a return trip and that is where Amy ran into a snag of illegal entry. My wife Ania who is fluent in Spanish was next to Amy and learned that the problem was that Amy didn’t have an entry stamp in her passport. We called our handler who in turn called people in Tikal, who called the airport there. The immigration people at the Mundo Maya said that indeed, they ran out of ink, and couldn’t stamp Amy’s passport, but not to worry, it was properly recorded in the immigration authorities’ computers. The officer in Aurora didn’t want to hear any of that, no stamp, no entry. That particular dance took about half an hour, at which point everybody was yelling at everybody, and finally the stubborn official gave up.

When you enter Mexico from the North, you don’t have to land at the first Airport of Entry, you can continue to any airport along your route of flight. That is very different when coming from the South, your options are limited to Tapachula and Cozumel, and from where we were, the former made sense. Our AIUs were received without problems, but they still asked us to haul our luggage to the office for an X-ray machine inspection. We arrived on a Sunday and Mexico just started applying special $150 weekend fees for immigration services, despite the airport being open and staffed 7 days a week since the beginning of time.

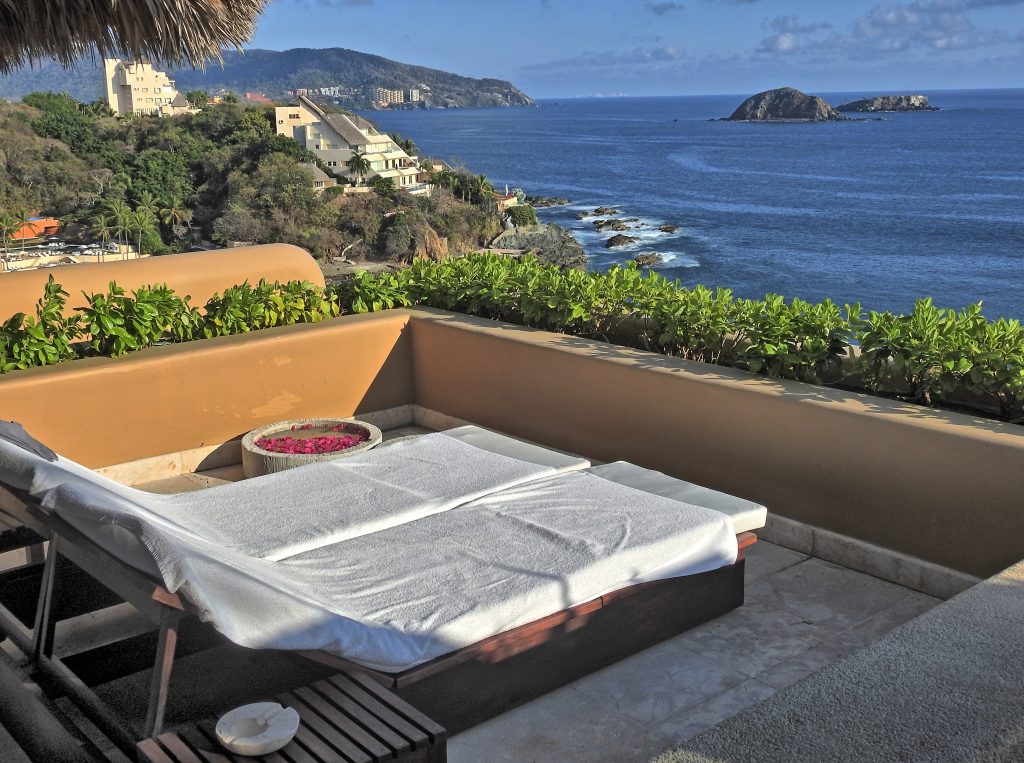

Our original plan was to spend a couple of nights in Acapulco, in the spectacular Encanto hotel. We made a group reservation and paid a deposit back in September, but then Hurricane Otis ravaged the city in October and destroyed the hotel. Nobody was answering phones or emails anymore, the airport was closed, and it was a disaster area. We made a new reservation at Secrets in Huatulco, which was nice, but far away from the elegance of Encanto. This was our last group stop and after two nights in Huatulco, everybody launched individually for flights back home.

Organized trips like this one are a great way to spread the wings outside our borders without the stress of dealing with different languages, different procedures, and unfamiliar rules. Flying in a group is easier and safer, we communicate on an air-to-air frequency about any unexpected issues, interesting sights, or ATC directions. A camaraderie developed during after the flight debriefings, which invariably take place in a bar, often persists well after a trip is completed.

Hasta el próximo año.