This is the third part of our trip, we flew from South Africa, through Mozambique to Zanzibar and traversed Tanzania East to West. This part is about close encounters with mountain gorillas and chimpanzees, also flying without fuel cap and fuel exhaustion. We were a group of friends flying in four Cessna 182 and 206 airplanes.

We left Mbali Mbali Soroi lodge when it was still dark and witnessed sunrise while driving to the Seronera airstrip.

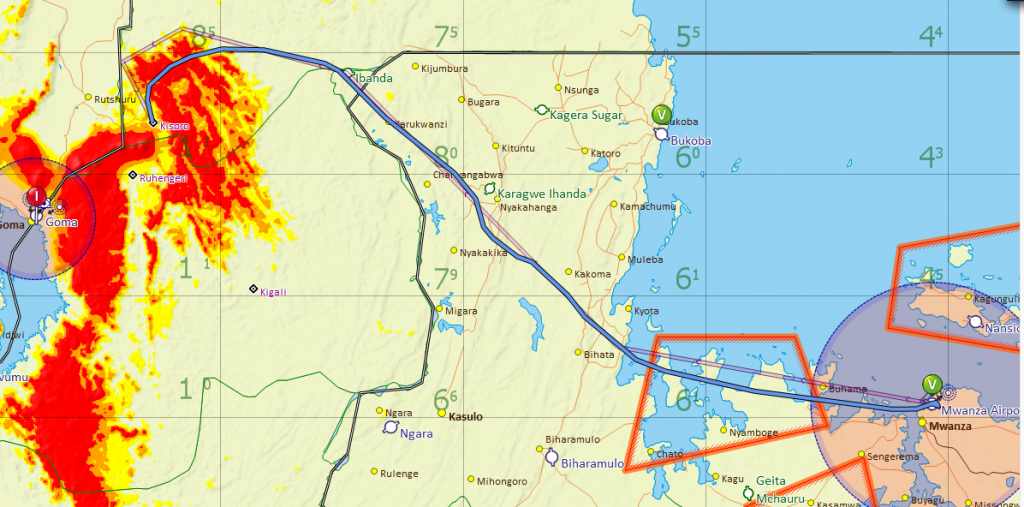

After a short flight Mwanza, refueling, customs and immigration, this time without taking suitcases out of airplanes, we launched for Kisoro in Uganda. There are quite high mountains on the direct line, up to 14,000 feet and we decided to fly around them to the North, which was a fortunate decision, because about half an hour after departure we got into an area of low ceilings and rain with reduced visibility. Let’s just say it was marginal VFR, although I usually call something like that “African VFR”. At one point we seriously considered turning around, but Chris who was flying first called with an update that weather was improving further north and we continued.

The solid red you see above, this is terrain higher than 7,000 feet. The African VFR happened about half way, so over relatively low terrain.

Flying over Bwindi Impenetrable Park we could see the mountains we were to explore the next day. Landing in Kisoro was refreshingly simple, there was an immigration officer already waiting for us, he efficiently stamped our passport, we didn’t have to pay anything extra in spite of the fact that Kisoro is definitely not an Airport of Entry. There was no customs, so nobody checked our luggage. We boarded vans for an hour ride to Mutanda Lake Resort.

Mutanda Lake is beautiful, with little islands sparkling in water and mountains around. The resort not so much, it is one of those places where internet photos are heavily photo-shopped. The next day we drove another hour to enter the park for the gorilla trekking. After a briefing about what to do when in close proximity to gorillas, we got an option to hire porters. I had just a backpack, so we thought one porter would be sufficient, but we hired two to support the village. This turned out to be the best decision of the day. The trek involved descending and climbing over very steep slopes in the jungle, lasted six hours and at the end, we were all beyond exhausted.

This snapshot from iPhone Health app says it all. Porters helped us not only with the backpack, but by literally pulling us uphill and holding us during the descents. If you ever do this trek, make sure you have one porter per person. We did manage though to get very close to the apes, within 3-5 feet and we could observe them for about an hour. They didn’t pay much attention to us and kept eating leaves. The alpha-male silverback was impressively large, even when seated. The effort spent to get that close to them made the whole experience even more precious.

We could barely walk next day, I was feeling muscles I didn’t even know I had, descending steep inclines makes you more sore next day than climbing, but we boarded the van again for a ride back to Kisoro airstrip. This time, customs was there and insisted on inspecting every piece of luggage, which was really driving me nuts. The field is at 6,200 feet and has a terrain rising to the south. We had between 10 and 15 knots of wind coming from the south, so we decided to takeoff in that direction, which turned out to be somewhat challenging. At Vx, I had an impression that the airplane is not climbing and that we will settle in the trees. Finally, we cleared the hills and flew back over the lake for some last-minute pictures. In hindsight, it would have been preferable to take off with tailwind. The flight to Kigali, capital of Rwanda was beautiful, in spite of strong headwinds.

On arrival the approach controller was querying us in flight about our permit numbers, upset that we were coming from Kisoro and not from Mwanza, as if that was important, told us first to turn to a heading which would send us into a hill (unable), then told us to fly a DME arc (unable, we were VFR), then told us to hold and finally switched us to tower, who cleared Robert to land while an airliner was taxing onto the runway for takeoff in the opposite direction. Clearly, Kigali is not used to VFR and light airplanes and indeed they have no avgas. We refueled from drums, which we had shipped there ahead of time and this is when I found that my left wing fuel cap was gone, again.

Remember departure from Wonderboom and losing the same fuel cap? I will never know if I was distracted and angry by the ridiculous luggage inspection in Kisoro and didn’t properly secure the cap after checking fuel level or if the cap had a problem, since it was the same one we lost in FAWB. I decided to turn this into a positive event, by promising myself I will never allow myself to become excited and emotional prior to takeoff. A mental trick I use now is to visualize that fuel cap whenever I feel I might lose focus. Lack of fuel cap presented us with two problems. How to secure the left tank and how to get from Kigali to Tabora, our next refueling point? We were supposed to fly to Kigoma (180 nm), then to Mahale (84 nm) and only then to Tabora (194 nm), total distance of 460 nm with three takeoffs, too far on only the right tank.

We resolved the first issue by the universal airplane repair tool: duct tape. While I wasn’t sure it would actually prevent fuel from leaking, there was only about 8 gallons left in the left tank and I was planning to only use the right tank. As to the second issue, when we were in Mwanza, we applied another universal rule for flying in Africa: when you see fuel, you take fuel and we filled four 20 liters jerrycans, just in case, without knowing it would become so useful so quickly. Twenty gallons in jerrycans combined with forty gallons in the right tank gave me an endurance of five hours, which was cutting it a bit too close with less than 30 minutes reserve. That problem was in turn resolved by stopping at a gas station in Kigoma and filling another twenty liter jerrycan with mogas. The 206 had a STC for mogas, but Marcus warned us to use the minimum necessary – in this case, we were only mixing 8 gallons of mogas with 40 gallons of avgas so I felt this was reasonable.

The flight from Kigali to Kigoma made us overfly Burundi. While we had overfly permits, we never managed to talk to Bujumbura Approach. Half over the country is covered by a TMA, so it was theoretically required, although it didn’t bother me at all we couldn’t. When arriving to Kigoma, I was trying to raise Kigoma tower on the radio. After landing, somebody finally replied asking why we didn’t call tower. I said we did, many times, on 118.4, frequency listed on Skydemon and Jeppesen charts, to which he replied “ah yes, we recently changed it 133.5”. Flying in Africa.

We stayed one night in Kigoma Hilltop Hotel, a comfortable but uninspiring hotel on the shore of Lake Tanganyika and after another security checks, launched for Mahale, one of the most stunning parks in Tanzania, with sand beaches, behind which rises a range of imposing mountains, clad in verdant tropical vegetation.

Mahale National Park is home to around 1,000 chimpanzees. Most significantly, one group of Mahale chimps – the Mimikire clan – has been habituated by researchers since 1965. Currently led by an impressive alpha male, Alofu, the M-group, as they are commonly known, has around 56 chimps. They go where they want and when they want but are relaxed near people, so it’s possible to track and observe them from very close quarters. For the good of the chimps’ health, all human visitors on chimpanzee safaris are required to wear surgical masks.

We stayed in Mbali Mbali Mahale, an idyllic lodge with luxurious bungalows, great food and very attentive staff. The next day we went to see the chimpanzees and I could still feel my legs after the gorilla visit. This was however incomparably less strenuous and we got chimpanzees passing couple of feet from us – not paying much attention to what we were doing, which was really just taking as many pictures as possible. In the afternoon, part of the group went for fishing and caught our dinner, but we stayed at the lodge, just relaxing.

Our last day started very early, with breakfast at 6 am and departure from the hotel at 7 am for 1.5 hour boat ride to the airstrip and 2 hours flight to Tabora. My fuel consumption was as planned and we arrived with comfortable margin. This time, I filled both tanks, but failed to follow the universal Africa fuel rule: when you see fuel, you take fuel – we didn’t fill the jerrycans. I put a little square of hard plastic made from plastic water bottle over the opening in an attempt to isolate the duct tape from the fuel and covered it with tape. We went thru usual hassles of immigration, customs, paying the fees and filing the flight plans and launched for the 4 hours flight to Mombasa. I was the first and immediately after the takeoff we noticed fuel streaming from the left tank.

I returned back to the airport and we attempted to put more duct tape over the wing. When satisfied with the result, we wanted to launch again, but the whole airport staff and a fire truck was there – the airport manager said he couldn’t let me go because the airplane was not safe. What followed was a ten minutes discussion, we were explaining that a Cessna 206 has two fuel selector position, left and right and even if we lost all fuel from the left tank, we still had enough to fly to our alternate, Arusha. Finally, he made me write and sign a release and agreed to let us go.

We couldn’t see fuel streaming on the second takeoff, so I hoped the tape would hold and it seemed it did for a while. Fuel gauge on the left tank was moving towards zero too fast, but then it stopped moving at a quarter tank. I set myself a limit – I was flying on the left tank and if I could delay switching to the right tank until 300 nm from the destination (about 3 hours with headwind we had), I would continue to Mombasa, otherwise I would divert to Arusha. Things were going on nicely, but then at 330 miles, engine stopped. That’s always an unpleasant event, but particularly when you are over middle of Tanzania with nothing but low brush below – lions and leopards are much less cute when observed from a crashed airplane. I was obviously spring-loaded for that situation, immediately switched to the right tank, fuel pump, and the engine restarted few very long seconds later. I now had dilemma – continue to the destination and land with couple gallons of fuel or divert to Arusha. In any normal country, it would be a simple call, but in Tanzania we already exited the country, Arusha is a domestic-only airport and I recalled experience of my friend John who declared emergency over Medellin, Colombia and was stuck there for four days resolving paperwork. I thought about it for couple of minutes, redid fuel calculations and announced on our air-to-air frequency that we were diverting to Arusha. My calculations showed that if reduce power and lean brutally, I most likely would made it to Mombasa, but with less than half an hour reserve and “most likely” together with “less than half an hour reserves” didn’t sit well with me. I didn’t have fuel totalizer. fuel flow indication was an analog gauge and I wasn’t 100% sure how accurate it was. I recalled another experience in Bogota, Colombia when I broke my one hour fuel reserve landing with 45 minutes and how I promised myself I would never do it again. Well, here I was again, what’s the point of making yourself promises and setting up limits before departure if you are not prepared to respect them?

All the others continued to Mombasa, they couldn’t help us in Arusha and in fact would have made the situation worse by having four, instead of one aircraft in an irregular situation. Approaching Arusha, I called Kilimanjaro Approach and explained that I had a fuel leak, I was diverting to Arusha to make a technical stop. After being cleared to land, we taxied to fuel and took 42 liters (11 gallons) into the right tank. I most likely would have made it to Mombasa, but most likely was not good enough. I went to the tower and explained the situation there, hoping they would let me leave on my existing flight plan. After few phone calls it became clear that they had no clue what to do with me, so finally they found a solution allowing them to get rid of the problem altogether. “This is a domestic airport, you are flying to Kenya, you need to receive the clearance from Kilimanjaro Approach”. Whatever was getting me back in the air was fine by me, so we back-taxied and took off. We called Kili Approach, who thought we were coming for landing at Kilimanjaro International, but I explained we were on the fight plan to Mombasa and they just requested we stayed at or below 5,500 when in the control zone.

When we left the CTR and I switched the frequency, we knew we were going to sleep in Mombasa that night. Soon we entered Kenya airspace and proceeded to the destination. The 30 minutes turnaround in Arusha will most likely remain a record hard to beat for years to come.

It was hard to believe this trip was now over. We flew 3,625 nautical miles in 34.4 hours Hobbs, landed at 19 airports in 6 countries and brought back 120 GBytes of pictures and videos. You can see the map on the right in more details on Google Maps.