Circling approaches topic was suggested on COPA Forums:

Best practices for circling approaches (which are apparently the highest risk).

And it was followed by this comment:

Simple—I don’t do ‘em. Too much maneuvering too close to the ground.

That will make it a very short article. I wish everyone blue skies. Ah, if only life were so simple. First, there are good reasons to fly circling approaches, and second, they can be done safely. Let me explain.

Before we get started, though, I should say that correct terminology is “circling minima” as opposed to “circling approaches”. If MDA for circling is specified on the approach chart, any approach may be flown as a circling approach. For simplicity, I will use the term “circling approach”.

A circling approach is any approach when the pilot flies an approach to one runway and maneuvers to land on a different runway, or the same runway, but not straight in.

Three reasons to fly circling approaches

The two airports I fly out of most often, SQL and PAO, have approaches to one runway only, 30 and 31, respectively. If the wind is from the South, as is usually the case with overcast over the Bay, the only option to get in is to fly the approach and circle to runway 12 or 13.

Even if there is an approach to the runway you want to land on, flying it may involve significant distance and time, which sometimes may be safely avoided.

If you prepare for the instrument checkride, you must practice circling approaches, which are in the ACS, and the examiner will ask you to fly at the MDA:

IR.VI.D.S5: Maintain airspeed ±10 knots, desired heading/track ±10°, and altitude +100/-0 feet until descending below the MDA or the preselected circling altitude above the MDA.

I described possible reasons to fly circling approaches, but how do you fly them safely? FAA TERPS criteria specify the lowest possible MDA on a circling approach as 350’ AGL for category A and 450’ AGL for category B. For fun, you can check out Point Hope airport (PAPO) in Alaska. Surely, flying downwind at 350’ AGL can’t be your definition of fun. Here, personal minimums come to the rescue. The fact that MDA is low doesn’t mean that you must fly it that low. My personal minimums for circling require a ceiling of 500 feet above pattern altitude and 1.5 statute miles (sm) visibility. With that kind of weather, it becomes an almost VFR pattern with a significantly reduced risk of having to fly missed (more about it later). Yes, it is riskier than the VFR pattern, but I am confident that I can fly the downwind at the pattern altitude. If this is too risky or too conservative for your taste, remember that these are my personal minimums, and you are free to adopt different ones.

Planning circling approach

How do you fly circling approaches? You must first recognize that they require more analysis and planning than straight in approaches. This analysis and planning is best done before the flight but may also be done while cruising. In any case, it must be completed before starting the approach.

With a straight in approach, you arrive at the DA, MDA or VDP and the runway is right there before you. Or it isn’t and then you go missed following the route depicted on the chart. If you fly on the autopilot, you could even enable NAV mode and the airplane will dutifully follow the missed approach. That might be slightly different depending on the FMS you have, but this is beyond the circling approaches topic.

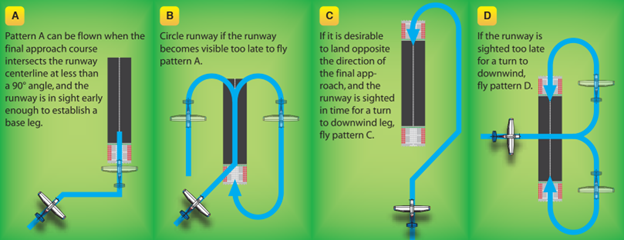

When you plan to circle, you must determine how you are going to enter the pattern, which will depend on the runway direction, your position and on the approach chart. FAA provides some examples of possible pattern entries in the Instrument Flying Handbook (p. 10-21)

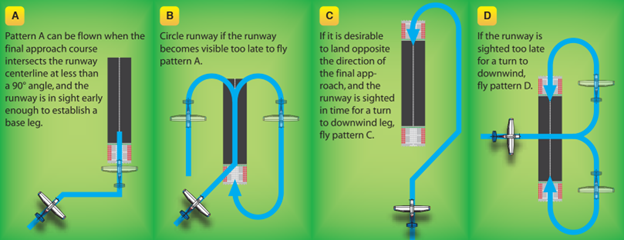

Let’s look at pattern B. Why would you want to fly that pattern? Consider the LOC 28L approach to Monterey Airport (MRY). You fly that approach while the ATIS publishes ceiling 3000’ and visibility 1.5 miles. Looks like quite reasonable conditions, doesn’t it?

You level at the MDA of 1860’ and motor along looking for the runway. You spot it at 1.5 miles out, precisely as the ATIS said, but you are now 1600’ above it. Assuming you fly at 100 knots, you would have to descend at over 2000 ft/min. That’s hardly what the FAA calls “landing at a normal rate of descent using normal maneuvers” in 91.175, which is why they publish a VDP (Visual Descent Point) 4.2 nm from the runway, and the AIM says in section 5-4-5 that “descend below MDA between MAP and VDP may be inadvisable or impossible”. So why didn’t they put the MAP where the VDP is? Precisely because you can circle to runway 28L using the pattern B and land safely using “normal rate of descent”.

In this example, you flew a circling approach, even though you were aligned for a straight-in approach. Make sure to inform the tower of your plans, or approach control if you determine it early enough.

Is the opposite also true? Can you land straight in even if an approach has only circling minimums? Yes, you can. Let’s take a look at the RNAV (GPS)-B at Henderson, Nevada (HND). Despite bringing you straight in and perfectly aligned with the runway, the approach has only circling minimums. The two main reasons why an approach has only straight in minimums are

- The final approach course and the runway are misaligned by more than 30° (15° for GPS approaches). That’s not the case here.

- Descent gradient from FAF to the runway exceeds 400 ft/nm. This is what happens here.

- There is a third, more obscure case related to runway markings.

It is 2130’ and 3 miles from FAF to the runway for the descent gradient of 710 ft/nm.

Can you land straight in? If you drop full flaps and fly at 80 knots with a 20-knot headwind, you will need to descend at 710 ft/min, which is certainly doable.

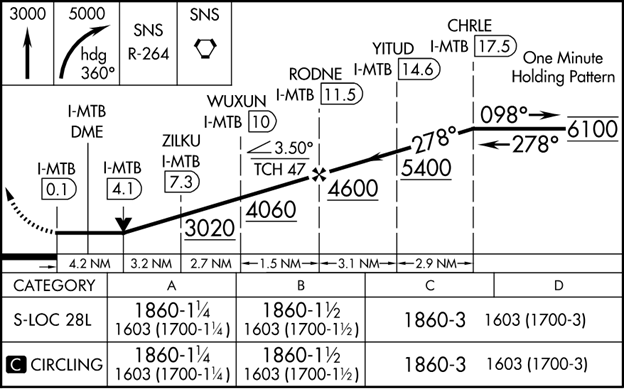

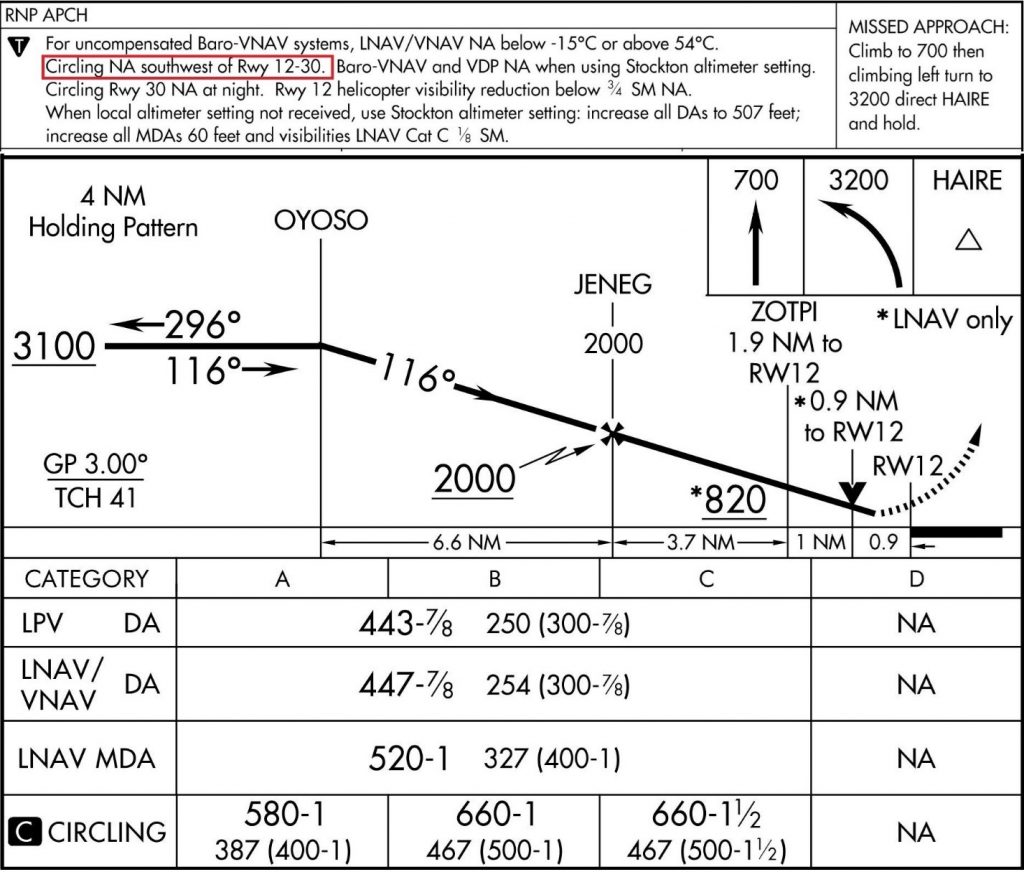

Keep in mind that if an approach offers only circling minima, you will not get an advisory glidepath. You can see this by noting that it announces LNAV, as opposed to LNAV+V, in the case of an RNAV (GPS) approach. To determine how to enter the pattern, you must also read carefully all the notes on the approach chart. Let’s have a look at the RNAV 12 to Tracy airport, assuming the AWOS says “ceiling 3000, visibility 10, wind 300/18”.

These are VFR conditions, and instead of flying out to join the RNAV 30, you decide to fly RNAV 12, circle to land 30. Since you land on the opposite runway, you plan to use pattern C. Checking the notes, you see that “Circling NA Southwest of Rwy 12-30”, which means that you must enter the right traffic pattern for runway 30. Great, but how about 91.126(b)(1), which says that

Each pilot of an airplane must make all turns of that airplane to the left unless the airport displays approved light signals or visual markings indicating that turns should be made to the right, in which case the pilot must make all turns to the right.

This means that traffic direction is mandated by FARs, and it doesn’t distinguish between VFR and IFR. You check the charts and find that Tracy has left the traffic pattern for all runways.

Which way will you circle? The FAA issued a legal interpretation (John Collins, August 2013) stating that pilots must follow traffic pattern directions in that scenario, at least for airports in Class G airspace. Since you can’t circle in the left pattern according to the approach chart notes and you can’t circle to the right according to 91.126, you cannot circle at all to runway 30. So why even publish circling minimums? Because you could circle to the other two runways, 26 and 8. On the other hand, that approach is often used in practical tests, and the examiners, who are FAA representatives during practical tests, fly the right pattern. There is an IFR Magazine article on that subject:

https://ifr-magazine.com/technique/which-way-to-turn/ As a practical matter, if the weather is as the AWOS indicates, there will likely be VFR traffic in the left pattern, and it would be prudent to fly the left pattern, canceling IFR if you wish to follow the rules. If the weather is down to minimums, then I wouldn’t fly the approach, but someone braver than I should choose to fly the right pattern, due to the risk of hitting obstacles in the left one.

Missed approach when circling

When planning a circling approach, also plan how you will fly the missed approach. This is simple as long as you are still on the straight-in part of the approach, because, well, you fly the same as for straight-in approaches. In a Cirrus Perspective, this involves TOGA with full power, flaps up, and NAV on the autopilot.

This becomes much more complicated if you have already started circling. I flew an IPC with a pilot some time ago, and the IPC tasks include a circling approach. We were planning to use the same RNAV 12 in TCY and circle to runway 30. The pilot entered right downwind, then base and final, when I said that there was a giraffe on the runway and we needed to go missed. Since the missed approach says, “climbing left turn to 3200 direct HAIRE”, the pilot dutifully turned left. This was, of course, the wrong direction, because when flying final to runway 30, he should have made a slight right turn, but he saw “left” on the approach chart and followed it.

Why did I say it was a giraffe? Because it happened to me once for real when flying in Africa.

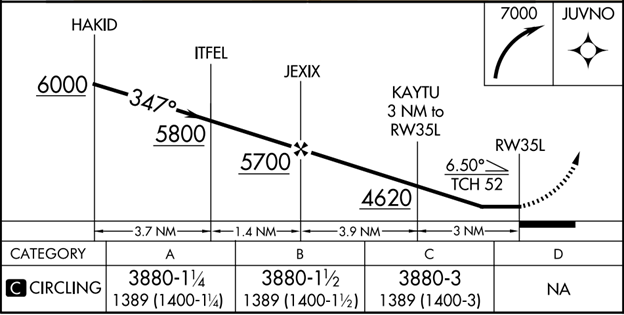

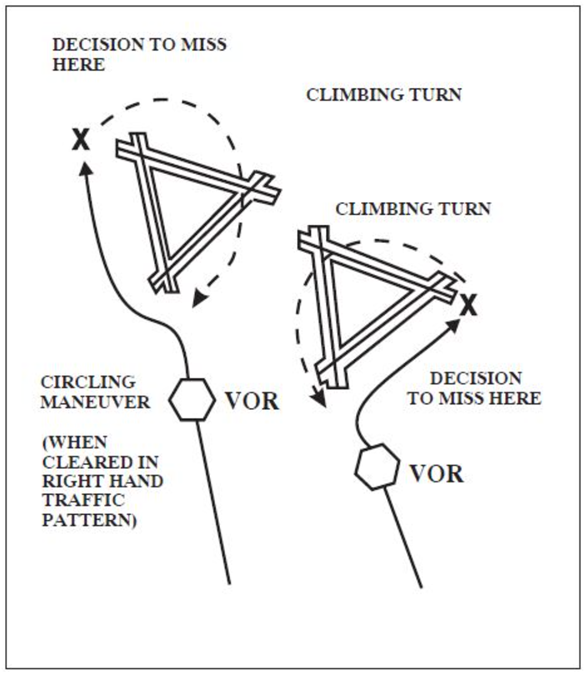

FAA has some helpful diagrams in the AIM, section 5-4-21:

If visual reference is lost while circling-to-land from an instrument approach, the missed approach specified for that particular procedure must be followed (unless an alternate missed approach procedure is specified by ATC). To become established on the prescribed missed approach course, the pilot should make an initial climbing turn toward the landing runway and continue the turn until established on the missed approach course. In as much as the circling maneuver may be accomplished in more than one direction, different patterns will be required to become established on the prescribed missed approach course, depending on the aircraft position at the time visual reference is lost. This is further illustrated in the following diagram.

These considerations make me want to eliminate or at least reduce the risk of having to fly the missed approach after circling, hence my personal minimums of ceiling at 500’ above the pattern altitude.

Protected areas

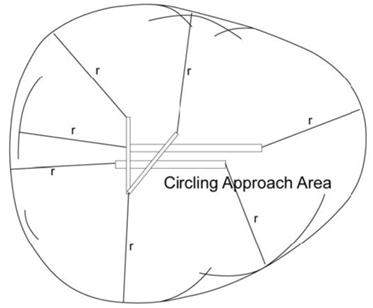

You may wonder how much area around the runway or airport is protected so that you don’t hit any obstacles. This leads us to a question: what is the meaning of the inverted C symbol on the chart, at the bottom left of the RNAV 12 TCY? The protected area is defined by the tangential connection of arcs drawn from each runway end.

You will have 300’ obstacle clearance as long as you remain within the protected area.

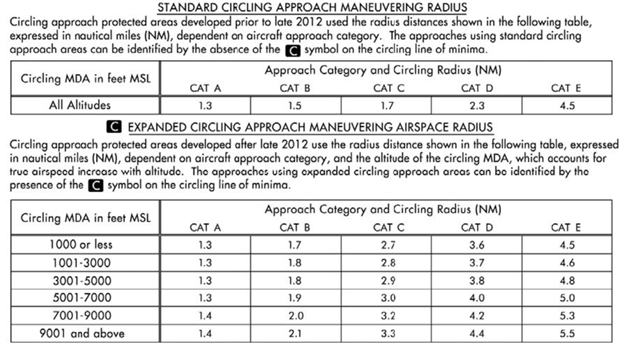

Circling approaches developed before 2013 used fixed radius distances. After that, the radius r on Figure 6 started to be dependent on the MDA, taking into account that the true airspeed increases with altitude. This is denoted by the “negative C” on the circling line of minima.

Figure 7. Size of protected area.

Aircraft Approach Category

Approach minimums define five aircraft categories:

- Category A: Speed less than 91 knots.

- Category B: Speed 91 knots or more but less than 121 knots.

- Category C: Speed 121 knots or more but less than 141 knots.

- Category D: Speed 141 knots or more but less than 166 knots.

- Category E: Speed 166 knots or more.

And AIM states that the category is based on Vref speed at the max gross, which, if not specified, is 1.3 times Vso. The Cirrus SR22T POH specifies Vref for short field landings as 79 knots. Does that mean we should fly as a Category A aircraft?

The very next AIM paragraph adds:

If it is necessary to operate at a speed in excess of the upper limit of the speed range for an aircraft’s category, the minimums for the higher category should be used. For example, an airplane which fits into Category B, but is circling to land at a speed of 145 knots, should use the approach Category D minimums. As an additional example, a Category A airplane (or helicopter) which is operating at 130 knots on a straight-in approach should use the approach Category C minimums.

The usual speed on the approach and downwind for a Cirrus SRXX is 100-110 knots; therefore, I recommend using category B minimums.

Visual Illusions and Electronic Help

By far the most common problem when learning to fly a circling approach is that the pilot flies downwind too close to the runway and overshoots the base-to-final turn. This is due to the same optical illusions that cause pilots to flare too high on a very wide runway.

Humans are not very good at judging distance and altitude; we are much better at judging angles, and we use that to infer distance and altitude using prior experience.

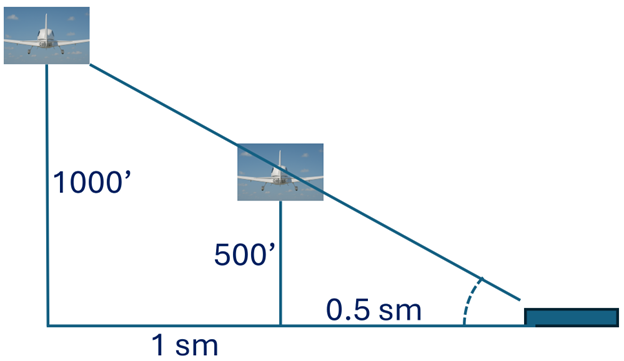

If you are used to seeing the runway at a certain angle when flying downwind at 1000’, you will be half a mile from the runway if you fly at 500’ and use the same angle as reference.

The same effect plays when turning base and final. Without compensating, you will turn base earlier than normal, and turn base to final later than usual, further exacerbating the overshot.

If you fly the approach in low-visibility conditions, you will also tend to fly closer to the runway than usual due to a phenomenon known as atmospheric perspective, also referred to as aerial perspective. This is because light scattering by particles in the atmosphere reduces the contrast and color saturation of objects, making them appear hazy and further away.

All of that may be eliminated with sufficient training, but you can also use equipment in the airplane to help judge the distance from the runway.

If you fly an approach to the opposite runway, which is well aligned with that runway, you can use cross-track error to monitor distance from the runway; it should ideally be between 0.7 and 1.0 miles in a Cirrus SRXX. You should add cross-track error (XTK) to the data fields on the MFD (Cirrus Perspective) or on your FMS (pre-Perspective aircraft). Note that while Perspective displays XTK on the HSI, it removes it when the CDI is completely deflected.

If you fly an approach that is at an angle different than 180° from the runway you intend to land, you can use the distance ring on the MFD to help you judge the distance. Be careful when using distance to the airport, as this refers to the distance to the airport’s reference point, which is often far from the runway.

Summary

I hope that short article helped demystify circling approaches. In summary:

- You must plan ahead how to enter the pattern and how to fly missed

- If there are only circling minimums, calculate the required descent rate, because you will not get an advisory glidepath

- You can land straight ahead from a circling approach if you determine you can do it with normal descent rates

- Fly category B minimums to remain in the protected area

- Determine and follow your personal minimums for circling approaches

- Be aware of optical illusions and use instruments to help

Happy circling.